The Butlin's Story by Norman Jacobs. Clacton History Society Chairman & local author.

The first indication that Billy Butlin was interested in building a holiday camp in Clacton came when it was discovered that he was a member of a business consortium which bought the West Clacton Estate in 1936. He very soon bought out his consortium partners and in the autumn of that year he presented Clacton council with the plans for his second holiday camp under the terms of the Town and Country Planning (General Interim Development) Order, 1933.

The application caused much controversy in the town. The people living at that end of Clacton thought it would lower the value of their properties; the hoteliers thought it would take trade away from then. On the other hand many of the town’s business welcomed the extra visitors it would bring. Butlin took all the Councillors to Skegness so they could see his other camp and explained that he used only local produce and local traders to service the camp and he would do the same for Clacton, so it would bring a lot of direct and indirect employment to Clacton. Eventually the proposal was passed by Clacton Council and building got underway.

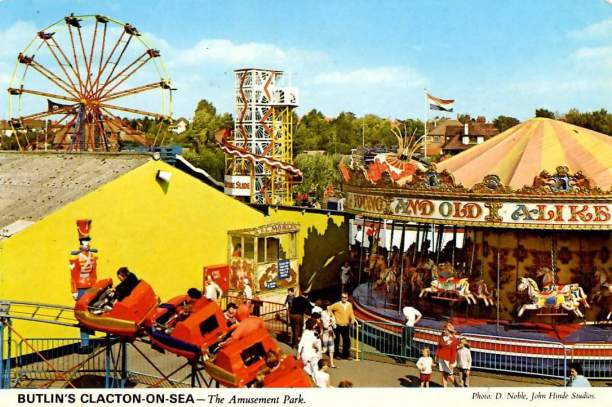

As soon as the council reached its decision, Billy Butlin went into action. He began to clear the site and started work on a new pleasure park. The building of the holiday camp itself was delayed but Butlin decided to go ahead and open the park to visitors for the 1937 season.

The pleasure park was an enormous success. Not only did it provide many thrilling rides such as swing boats which turned right over; a gravity glide; dodgems; the loopoplane and the big "Eli" wheel, the largest in the country, but it also put on many freak shows and speciality acts. including DareDevil Peggy, a 56 year old onelegged diver who dived from a height of 65 feet enveloped in flames into a blazing cauldron five feet deep, and the Stratosphere Girl. The Stratosphere Girl, whose real name was Camilla Mayer, was one of the most remarkable and popular acts ever to appear in Clacton. Her act consisted of performing extraordinary stunts perched on a two inch wide platform on top of a steel pole 135 feet high. On this platform she would stand on her head, on her hands, or on one toe. She brought her act to its climax by sliding along a rope from the pole to the centre of the park holding on by her teeth.

By the time the holiday camp itself opened on 11 June 1938, Butlin's was already a familiar name in Clacton and what little opposition there still was had been effectively silenced by the overwhelming support now apparent for Billy Butlin throughout the town. He was providing the right facilities and atmosphere to help turn Clacton into a booming holiday resort and his public relations machine had been working overtime to ensure that he carried the people of Clacton with him. He laid on a grand ceremonial opening for the camp and laid on a special train to bring 200 V.I.Ps down from London. The camp was officially opened by Lord Strabolgi, though it was left to another speaker, Lord Castlerosse to verbalise the thoughts of all present when he solemnly announced that "Billy Butlin has done more for England than St.George".

When first opened the camp provided accommodation for 1000 holidaymakers. Although only four hundred arrived for the first week the camp was fully booked for most of the season and further building was already underway to provide a further 500 places.

The highlight of the first season came during the week of 3 9 July, when a 'Festival of Holiday Health & Happiness' was held. This was open to nonresidents as well as residents at a daily cost of 1/. Special events included exhibition boxing by the then British light heavyweight champion, Len Harvey, exhibition tennis by Dan Maskell, a snooker tournament for the grand prize of 100 guineas between Joe Davis and Horace Lindrum and a demonstration of ballroom dancing by Mr. and Mrs. Victor Sylvester. The whole week culminated in a concert broadcast live on the BBC starring Elsie and Doris Waters, Vic Oliver, George Robey, Will Fyffe, Hildegaarde, Lew Stone and Mantovani with his Tipica Orchestra.

At the end of that firt season the Gazette was able to report that the camp had been a "greater success than ever imagined" both in terms of the camp itself and its acceptance into the town. Following the closure of the camp to holidaymakers for the season, Billy Butlin decided to open its doors to Clacton residents on Wednesday and Saturday evenings. This was a service to the townspeople which continued until well after the Second World War and one which is still fondly remembered by many Clacton inhabitants as the high spot of their social week.

New improvements for the 1939 season included 1,000 rose trees, a bowling green, six new shops, open air rollerskating, a miniature railway and an £8,000 electric organ installed in the new dance hall.

As Britain slipped closer and closer to war with Germany minor disruptions upset the smooth running of the camp. The Tannoy system was continually interrupting its entertainment broadcasts to give the names of men who had to report back to their home town for callup.

As soon as war was declared the camp was emptied and it was first of all handed over to the Air Force and then to the Army for use as an internment camp. Some chalets were demolished to allow for a barbed wire perimeter fence to be erected with floodlights every few yards. However, as there weren't many internees the camp was soon given to the Royal Auxiliary Corps, later the Pioneer Corps. The army continued at the camp in one form or another until the war ended, when it was handed back to Butlin's.

The camp was ready in time to open for the 1946 season and opened on 6 April with 800 guests. Even on that very first weekend after 6 years occupation by the military, a number of top stars were lined up to entertain the campers. There was the mind reader Maurice Fogel, Wally Goodman the comedian and Terry Thomas, billed as an impressionist.

The East Essex Gazette of 12 April took its readers on a tour of the camp: “[there are] rows of brightly coloured chalets with gardens between each row. There are shops, a post office and "Radio Butlin's". A gay nursery with toys and rocking horses is provided for the children who are all labelled to ensure they do not get lost. For casualties there is a sick ward. What was formerly the sergeant's mess is now a bar the Jolly Roger...The ballroom, one of the finest in England, has protruding fairy tale castles as the walls and Tudor pillars supporting a centre balcony…The dining room has plastic table cloths of many colours; food is brought in on electrically heated trolleys. There is a splendid gym with a boxing ring. Indoor entertainments include a theatre, billiards room and sun lounge and outofdoors there are tennis courts, a bowling green, swimming pool and fountain...In the mornings 'Cappie' Bond and an army instructor take voluntary P.T. classes, while a sympathetic trainer takes the children.”

Following advertisements in the local press for staff including typists, clerks, waiters, waitresses, cooks, kitchen hands, chalet maids, cleaners and handymen, the camp was inundated with 17,000 applications for jobs, of which 550 were successful.

For most of the rest of the first postwar season, Butlin's was full and the camp took up more or less exactly from where it had left off in 1939. There was no question now that it was part of Clacton, though there was still the odd minor hiccup as when the amusement park manager was fined £1 for “using a musical instrument worked by mechanical means (i.e. a hurdygurdy) to be played to the annoyance of residents between June 1st and 3rd”

The period between 1946 and the late 1950s, possibly the early 60s, were certainly the halcyon days of the holiday camp and Butlin's at Clacton was no exception. After six years of war, people were looking for the opportunity to let their hair down and enjoy themselves; holiday camps gave that opportunity. They were not too expensive and everything was provided for one allin cost. Food, entertainments, amusements, competitions, even a chalet maid to make your bed was all paid for at the outset. In theory you could go to Butlin's with no money at all in your pocket and still have a good time.

Special clubs to cater for children were formed - the Beaver Club and the 913 Club. These provided their own activities to allow their hardpressed parents time off to enjoy themselves on their holiday in their own way. This was the era of the knobbly knees, the glamorous grandmother, the Tarzan lookalike and the spaghettieating competitions. The prewar favourites such as the fancy dress competitions and the field sports also continued.

Although the competitions seemed to characterise the success of Butlin’s, it was ironically this form of activity which drew the most criticism of a Butlin’s

holiday after the war. Such criticism went along the lines of the complaints about 'strict regimentation’ and having to join in the fun and games whether you wanted to or not.

Defenders of Butlin’s pointed out that of course all the games and activities were laid on, but campers could take part, watch or ignore them as they wished. No one was ‘forced’ to do anything. Billy Butlin himself made the point that after the war no one would have stood for any more regimentation; it was exactly what everyone was trying to get away from. For most women it meant a week's freedom that they had never experienced before. As people became more affluent through the 1950s more and more families were going on holiday and enjoying the luxury of being waited on hand and foot. Meals were laid on, chalets were cleaned, beds made, and nurseries were provided, chalet patrols listened out for crying babies at night. It was not regimentation that Butlin's brought. It was freedom on a scale undreamed of by most people in the 1930s, when the nearest many got to a holiday was to go hop picking in Kent or on other types of working holiday if they went at all.

Many who were later to be stars and household names had some of their early entertaining experience at Butlin's Clacton either as red coats or resident singers and comedians. Names such as the Beverley Sisters, Michael Holliday, Jack Douglas, Ted Rogers, Dave Allen, Roy Hudd and Cliff Richard, who had his firstever professional engagement at Butlin's, Clacton all appeared on the camp in their younger days.

By the late 1950s, Butlin's had become a national institution and to some extent Clacton was able to bask in its reflected glory. The combination of Butlin's and Clacton had become firmly established and for both their futures as family holiday venues seemed unshakeable.

But the glory days of Butlin's were not to last for ever and during the 1960s the process of change which would eventually lead to Butlin's closure and Clacton's decline as a leading seaside resort gathered pace. The very affluence which had led many families to sample the delights of a week's holiday for the first time in their lives by choosing Butlin's, Clacton was now to lead them to eschew the very idea of going to Clacton or to a holiday camp.

Most of Butlin's trade had come from the East End of London, a mere 75 miles away, and most of the rest from the Midlands. Two weeks holiday came to be increasingly the norm, and with the extra time people wanted to go further afield. It was within the budget of many families now to go abroad to Ostend, Paris, Spain. British resorts were hard put to retain their clientele. Many campers who had returned year after year with an unswerving loyalty to Butlin's at Clacton were now beginning to desert the camp as the British way of life began to change.

By 1968, when Billy Butlin retired, family groups at the camp had fallen to an alltime low. Their place had been taken by large groups of single teenagers who, as a generation for the first time, had plenty of money in their pockets and were able to spend it largely as they pleased. Ironically this new generation discovered all over again the idea that Butlin’s gave them the freedom they desired and allowed them to escape from the disciplines of home, school and work. In a manner of speaking the wheel had come full circle, but this time, the new chairman of Butlin's, Billy's son Bobby, was concerned that the new style freedom had gone too far.

The camp's reputation had reached an all time low as teenagers, perhaps for the first time in their lives, discovered a place where they could indulge in the excesses of drink and sex with very little control over their activities. There were stories of all night parties, drinking, vandalism, gangfights and chaletswapping. Bobby Butlin therefore launched a programme of modernisation by building chalets with private bathrooms and converted large numbers of existing chalets, equipping them with cookers and fridges so that he could begin providing selfcatering holidays. Even for those campers who still wished to eat their meals in the dining hall, Butlin's now only provided breakfast and an evening meal. Fast food outlets were opened on the camp and campers were thereby given the option of eating the meals provided in the dining hall, buying their meals at one of the retail outlets or of cooking their own. The wearing of badges, an outward sign of the outdated regimentation, was also stopped. These changes had their effect, bookings picked up and in 1971 Butlin's enjoyed a record year.

However more changes to the familiar style of the holiday camp were just over the horizon. In 1972, Butlin's was taken over by the Rank Organisation and in 1977 and a number of changes made. The redcoats too were given a new rôle as times changed. The old house system was abolished and the camp merely divided into red camp and blue camp to differentiate between the selfcatering guest and the halfboard guest. The redcoat rôle as partisan house supporter urging the campers on to superhuman efforts to gain house points therefore had to change and they became the upfront public relations representatives of the Butlin's organisation dispensing information and goodwill. They were no longer forced to crack jokes every second of the day!

By 1980 Butlin's reached new heights with yet another record year for visitors. Owing to a continual programme of building, the original 1,000 capacity of Clacton Camp had grown to 6,000 and everything looked set for a bright future, and as the camp closed its doors on the 1983 season, there was no hint of the disaster to come. Seasonal staff were offered contracts for the following season and in the current edition of "Butlin News", Peter Wilson, the Bookings Manager for Clacton said he was looking forward to 1985, “the year in which he expects to get a computer to sort out his allocation section.”

But in the offices of the Rank Organisation, other changes were being dreamt up to streamline and modernise Butlin's. Holiday camps were a thing of the past. The word camp gave the wrong image of the modern holiday, so whole new "holiday centres" and "holiday villages" were to be created. All chalets were now to be the height of luxury with wall to wall carpeting, colour televisions, teasmaids and private bathrooms. To pay for these improvements Rank decided that something had to go, and that something was the camps at Filey and Clacton.

In a press statement Bobby Butlin summed up the decision by saying that a review had been carried out “with a view to planning for the future development of Butlin's. As a result it was decided that these two centres are no longer viable and regrettably they must close. We deeply regret having to take this painful decision and the effect that the closure will have on the staff of both centres and on the community.”

It was the end of an era for Clacton, brought about by a corporate investment decision based on hard economic facts with little time for nostalgia or the local impact of that decision.

In all the closure meant the loss of 100 permanent jobs and 841 seasonal jobs. A devastating blow to a town which already had one of the highest rates of unemployment in South East England and virtually destroyed the last vestiges of Clacton’s reputation as a onetime leading British holiday resort.